There’s Nothing Like Memoir of a Snail - Just Try Not to Cry

Years in the making, Academy Award winner Adam Elliot brings a new animated tale to the screen – and you’re gonna need the tissues.

good.film

a year ago

Share

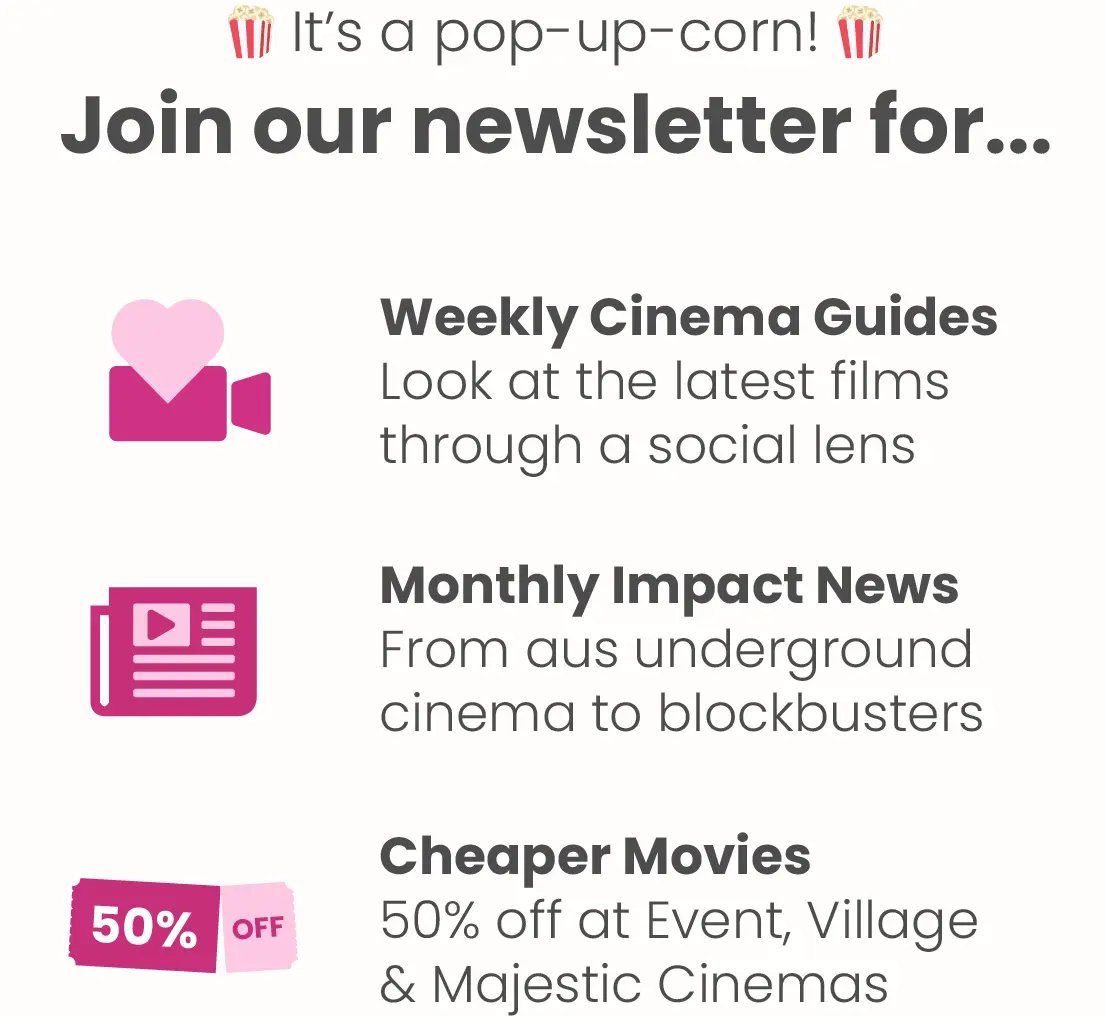

Want a great deal to catch Memoir of a Snail in cinemas?

GRAB YOUR DOUBLE PASS DEAL HERE!

Think “animated movie” and we can pretty much guarantee you’re thinking about explosively colourful outings for kids. Trolls, ogres, pandas, ponies, Italian plumbers, you name it – Hollywood’s brought them all to life, and used just about every animal in the zoo doing it.

But hey, not every animated movie is designed solely for children. Adult-themed stories brought to life by hand are often treasures: take the Oscar-winning work of Miyazaki, Guillermo del Toro’s wondrous reenvisioning of Pinocchio or even Charlie Kaufman’s surreal and sexual Anomalisa. As animators are fond of saying, animation isn’t a genre – it’s a medium.

Someone who’s always exploited that medium to its fullest emotional potential is Melbourne animator Adam Elliot. His style is unmistakable. From Harvie Krumpet to Mary & Max, Elliot’s instantly recognisable “clayographies” as he likes to call them, all share three things: a wonky handmade charm, a (predominantly brown) colour palette just oozing Australiana, and a strange habit of worming their way into audiences’ hearts.

What is Memoir of a Snail about?

Dreamlike? Odd? Truly WTF? Bingo! At heart, Memoir of a Snail is a funny, bittersweet remembrance of a lonely woman called Grace Pudel (pronounced “Puddle”, but she’s not shallow). She’s a quiet misfit with an affinity for collecting ornamental snails. Or maybe scratch “affinity” and make that “an obsession”.

Grace (gently voiced by Aussie Emmy-winner Sarah Snook) adores snails so much, she ends up retelling her life story to one: a humble garden snail named Sylvia. Which is lucky, because we get to listen in. We learn all about her 1970s childhood, and discover how Grace gets separated from her pyro-maniacal twin brother Gilbert (Kodi Smit-McPhee), falls into a spiral of anxiety and angst, and retreats into her shell. Hark, is that a metaphor we see?!

Despite her somewhat heartbreaking life – including a marriage with a very specific kind of gaslighting – a glint of hope emerges when Grace meets Pinky (Jacki Weaver), a gritty, eccentric old lady with a lust for life (and topless tap-dancing). Their friendship turns Memoir of a Snail into a life affirming, gently bonkers tale of an outsider finding the confidence to emerge from that shell.

How does Memoir of a Snail look at childhood trauma?

Aside from a truckload of brown plasticine, something else you wouldn’t expect from an animated film is to take inspiration from 19th-century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. But there it is, right there in Memoir of a Snail’s tagline: “Life can only be understood backwards, but we have to live it forwards.”

How apt then, that Elliot tells Grace’s story in flashback. To understand Grace, it’s important that we meet her right from the beginning – in utero, in fact, where she bobs alongside her twin brother Gilbert. In trademark Adam Elliot fashion, he laces cuteness with poignancy when Grace tells us, as an adult: “See? I wasn’t always this alone.”

Like most twins, Grace & Gilbert are inseparable; that’s cemented when Gilbert takes on the role of Grace’s protector, defending her from the bullies at school who mock her cleft lip. They’re each other’s allies, growing up in a very poor household – their Mum died in childbirth, and their Dad is a wheelchair-bound alcoholic… we DID mention this movie ISN’T for kids, right?

Still, they’re happy. As Grace tells Sylvia the snail, “I believed in glasses half-full. Then, my glass was shattered.” When their Dad dies early in the film, it sets a lot of things in train for Grace. The loss of her only parent triggers an interest in collecting snails which becomes a troubling obsession. And in an act that seems horrifying today, Child Services send Grace and Gilbert away to different foster homes, in different states, thousands of kilometres apart.

This is a real phenomenon: research estimates that nearly two-thirds of foster children are separated from their siblings. What Elliot captures beautifully here is the sheer heartbreak that Grace feels being cut off from her only lifeline, her twin brother (can you imagine?), and how that trauma colours the rest of her upbringing into adulthood. “Losing a twin is like losing an eye,” Grace explains to Sylvia. “You never see the world the same way again.”

🐌 MEMOIR OF A SNAIL TRIVIA 🐌

- The animators captured over 135,000 photographs to create the film

- Every single object in the film is a real, tangible object - there is zero CGI

- There are over 3000 handmade ornamental snail objects in Grace's hoard!

What about issues like anxiety and hoarding?

As an adult, Grace seems to have a small life. She lives alone, dresses strangely, and picks up odd jobs, like at the local library. She borrows romance novels and reads them surrounded by the thousands of snail-themed knick-knacks in her house. Looking in the mirror, Grace literally imagines herself as a snail: monotone, curled-up and silent.

It’s not a stretch to suggest that Grace is drawn to snails because they come with their own tough protective coating. One that she’s been missing since she lost her brother, the defender. What’s left is the squishy, vulnerable person inside the shell. Either as armour or as comfort, Grace has surrounded herself with escargot to subconsciously fill the void.

Made infamous on reality TV shows, hoarding is a serious (and still under-recognised) mental illness that can worsen with age. The University of NSW found that hoarding affects 2.5% of the working-age population and 7% of older adults. That’s about 715,000 Australians. While there’s no one single “cause” for hoarding, research has shown that emotional deprivation as a child can play a strong role.

The way that Adam Elliot makes us keenly feel Grace’s vulnerability OUT OF CLAY is nothing short of a miracle. So when Grace is wooed by Ken (Tony Armstrong), an unlikely suitor that loves her curves, our red flag radar is up. Ken claims to love Grace just as she is – but he’s up to something behind her back that equates to another form of abuse. Cue a further spiral.

Thank goodness for the unpredictable Pinky, a library visitor who Grace ends up describing as “the only colour in my life”. With her sheer bravado and wildness, Pinky is everything Grace is not – and she creates a new lifeline for Grace back to the “real world”. Elliot’s not suggesting that anxiety or mental illness are magically solved by making a new friend, but he does give Pinky the sensitivity to coax Grace into making a gentle change. “The worst cages are the ones we create for ourselves,” she reminds Grace. “It’s time for you to shed your shell.”

“Why do we collect unnecessary things and when does that become a problem? The psychology behind why we carry these items through our lives is something I'm curious of. I read many books on hoarding, and I learnt how extreme hoarders have often had a traumatic loss in their lives; the sudden death of a family member and often, a child.”

~ Writer/Director Adam Elliot

How does Memoir of a Snail find the funny within darker themes?

Of course, tons of movies have the power to make us cry. But there’s literally no other sense of humour on film quite like Adam Elliot’s. “I love adding quirks and idiosyncrasies to my characters' psyches and try and give them incongruities and dimension,” Elliot describes. “I try to get a balance between light and shade, comedy and tragedy.”

Mission accomplished. Every design has a lumpy imperfection that’s instantly likeable; each dry put-down is as Aussie as a Chiko Roll in a ute in a tropical hailstorm. For Elliot, darkness is a more fertile soil that makes the funny even more nutritious (in one scene, the fire-loving Gilbert “accidentally” burns down the church of his cruel, religious fundamentalist foster parents – trust us, you’ll cheer).

It’s in Pinky that Memoir of a Snail finds most of its laughs, laced like gems through the heavier scenes. She’s eccentric, risqué and self deprecating, with a penchant for yelling “dickhead!” at passing hoons. The kind of lady who’s playing ping pong with world leaders one day and handing out pineapple samples (while dressed as a giant pineapple) the next. Grace regards Pinky in a kind of wonder; in an odd way, she’s a stand-in for the mother she never had.

It’s worth repeating: don’t take little kids to this film. Aside from everything we’ve touched on, there’s sexual references and swear words everywhere (not to mention a few flashes of clay-based nudity from time to time)! But they’re not added for shock. Like the rest of the DNA in Elliot’s work, there’s an innocence to the “rude bits”; a warm & fuzzy flavour that leaves you with a grin.

“The protagonists in all my films are outsiders and my themes and narratives explore difference. I love telling stories that are infused with humour and pathos; stories that celebrate the moments of joy with the darkness that comes with life's challenges.”

~ Writer/Director Adam Elliot

What are critics saying about Memoir of a Snail?

“Elliot is a master of the art of gallows humour … as hilarious as it is heart-wrenching.”

- Wendy Ide, Screen International

“Sorrowful and poignant, but above all uplifting, this is a love letter to family of all shapes and sizes.”

- Lisa Nystrom, FILMINK Australia

“Elliot time and again marries darkness and light, sweetness with sour to create a satisfying emotional umami.”

- Amber Wilkinson, Eye for Film

So what’s the takeaway from Memoir of a Snail?

While its scale is miniature, the human concepts breathing inside Memoir – childhood trauma, mental illness, grief – are large enough for a Cinemascope widescreen. And it might sound bizarre that in a story featuring drunken jugglers, decapitated fingers and fornicating snails, the feelings are somehow universal. But Elliot’s characters, brought to painstaking life one frame at a time, seem to have an ability to tap into almost anyone.

Haven’t we all felt like the outsider at some point? The weirdo, the one with secret habits? Or even the one who never expects to find love, because we don’t think we have any qualities that deserve it? In its heroine Grace, Memoir of a Snail personifies that little doubting voice inside all of us – and then Pinky tells it to “bugger off!”

Honestly, it feels great to laugh straight after you’ve just welled up. These characters and their pain feel authentically real to us, and even though Elliot includes jokes, he doesn’t joke about them. He lays them bare to us with respect, and imbues his odd menagerie with… well, with dignity. Which is a funny thing to say about something with plasticine eyeballs and glycerine tears.

“They may be just little blobs of clay,” says Elliot, “but to my team and I, they are real people. We truly hope their little lives give meaning, joy, and comfort to those who watch.”

Want a great deal to catch Memoir of a Snail in cinemas?

GRAB YOUR DOUBLE PASS DEAL HERE!