Yes, It’s Okay to Laugh at a Holocaust Movie

A Real Pain is a warm and worthy addition to the Holocaust film genre. And it’s damn funny to boot.

good.film

a year ago

Share

Think ‘Holocaust film’ and that movie screen in your brain might flicker to life with bold and searing images like the little girl in the red coat amidst the desaturated masses of Schindler’s List… a gaunt Adrien Brody in his Oscar-winning role as The Pianist… or the shock and grief of Meryl Streep as she makes her fateful decision in Sophie’s Choice.

What you’re probs NOT visualising is the nerd from The Social Network awkwardly navigating a tour of Poland with the man-child who brought Succession’s sassiest billionaire-in-waiting to life. And yet A Real Pain – written by, directed by and starring Jesse Eisenberg – is a warm and worthy addition to the Holocaust film genre. And it’s damn funny to boot.

As mismatched cousins, David (Eisenberg) and Benji (Kieran Culkin) head to Warsaw to honour their recently departed grandmother. They want to pay their respects to the horrors she escaped, and the homeland she fled. They’re getting in touch with the past and their roots. They just weren’t expecting to dig up so many prickles and thorns from the present.

We ‘get’ their personalities immediately: Benji is loose, sweary, carefree and probably ADHD. The kind of guy who says I got you a yoghurt! and then hands you the pack warm from his pocket. David is wayyy up the other end of the scale: careful, nerdish, stammering and hyper-aware of social mores. A triple-checker. An anxiety-meds guy.

Eisenberg uses the first few scenes to casually set up these cousins’ deep family ties along with their differences. They used to be tight, almost brothers. And their odd couple chemistry is still there (an early laugh comes when Benji compliments David’s bare feet, saying they’re graceful as f**k! and they remind him of their grandmother’s). So what drifted them apart? The answer, of course, is drip-fed as the film plays out.

Another question is tone: in a Holocaust story, just how comic is Eisenberg prepared to go? One of the film’s huge strengths is its screenplay, and as it unfolds, it’s obvious that the balance of serious subject and prodding satire is respectful and deft. It’s no surprise that the Jewish people rely on humour as a coping mechanism. But here, it’s also a narrative tool; the characters wonder aloud if it’s okay? to deploy humour in the aftermath of tragedy.

Like when David oversleeps their train stop, and they lose their tour group. Cue a gold scene where Benji teaches his cousin how to dodge fare inspectors – and drags him out of his shell. Benji justifies the cheeky move with Hey, this was our country, we can ride for free! David’s dry reply is a line straight out of Woody Allen’s typewriter: Yeah, it WAS our country – they kicked us out because they thought we were cheap.

One of the core ideas Eisenberg is playing with in A Real Pain is the whole concept itself of so-called tragedy tourism. Is it the right thing to trot around with cameras at places where so much anguish took place? Isn’t it a bit ick that tour groups travel in first-class train carriages, to ‘honour’ their forebears – who were stuffed into the back? In the film, the sped-up and super emotionally available Benji is the proxy to jab at this edgy juxtaposition.

It’s actually this quality in Benji that makes David uncomfortable around him – he seems on guard. He regularly apologizes to others for Benji’s blurted out comments, and he’s irritated that Benji bonds with other people so easily, despite being so unconventional. Benji’s carefree and non-inhibited, and he often leaves David aghast (case in point: Benji flinging his shoes & socks off and skipping through a Polish memorial pond).

But the clever flip is that, while David’s the ‘proper’ one, he’s not leaning into the experience. Benji is the one creating emotionally authentic moments that resonate, for himself and others. Like at an enormous monument to the 1944 Warsaw Uprising, shot in Krasiński Square, where David is hesitant to take snaps of Benji posing next to the statues frozen in battle. It feels… disrespectful? But one by one, Benji convinces the rest of the group to join in, and they find a kind of catharsis and connection in their roleplay – everyone except David, who watches on.

Naturally, Eisenberg is keenly focused on generational trauma through A Real Pain. How do the stories and implications of the Holocaust continue to impact characters like David, Benji and their families? Is there a sense of guilt that their lives are luxurious, even ludicrous, compared to their grandmother’s generation? (When David reminds Benji that he’s in digital ad sales, Benji immediately replies, Oh yeah, everyone hates that internet banner bullshit).

Their tour guide James (Will Sharpe) compares Warsaw to a phoenix, risen from the ashes, and reassures the group that while this is a tour about pain, we’ll be celebrating the people.

But after an endless string of facts and stats, Benji calls him out: he’s ignoring the real people and their real stories behind the tragic sites they’ve been visiting. They’ve seen a lot of buildings and statues, but they haven’t actually spoken to a single Polish person.

For David, it’s mortifying; another example of his black sheep cousin making a public scene. Why are you doing this?! But James genuinely thanks him, saying You're the first person to ever give me actionable feedback, and you were right. The insight? Prodding at wounds might feel painful, even wrong, but honesty and genuine emotional openness will trump sterile platitudes every time.

Benji puts it a different way: We're on a f**king holocaust tour, if now isn't the time to grieve and open up then I dunno when is. And they’re not empty words. After the group tours the Majdanek death camp (A Real Pain is the first narrative feature given permission to shoot there), Benji openly sobs on the coach ride home. In contrast, David sits silent and numb.

It’s tempting to wonder if the medication Dave pops throughout the film is blanketing him from really feeling the pain. Later, Benji interrogates that difference – and by extension, the distance between them – saying to David, You used to cry at everything! You used to feel everything! (David snaps back, Yeah, and it was awful!) On the surface, Benji’s asking what happened to you? but really he’s asking, what happened to US?

It’s where A Real Pain starts to fold in its true allegory, using the grief and loss of the Holocaust as a backdrop to the modern-day grief and losses we experience today. In one scene, David panics when Benji doesn’t get back to their hotel room overnight, jumping into the ‘protector’ role. Initially, we put it down to personality; David’s anxious, a worrywart who doesn’t go with the flow. But we soon learn Benji put them both through a near-death experience six months earlier, and it’s a frightening scar that David still carries around with him.

It’s certainly a mental health-forward film, touching on depression (Benji), conditions like OCD (David) and personal struggle. They’re each inwardly envious of the other: Benji doesn’t have a stable career like David (even if it is ‘bullshit’), and he looks at David’s videocalls home to his young son with a kind of yearning. On the flip side, you can tell David pangs for even an ounce of Benji’s joie de vivre, sharing with the group I would give anything to know what it feels like to walk into a room and charm everyone. He's so cool and he doesn't give a shit.

Ultimately, it’s this exact trait that gives A Real Pain its uniqueness (and a potential Oscar win for Culkin – watch this space). On paper, Benji’s qualities are the last things you’d want on a solemn Holocaust tour. Being here with him is so baffling, David admits. How did this guy come from a place of these survivors?? But he uses those same qualities to naturally open people up and bring them together.

The irony for Benji is that living so openly causes him far more pain than those who shut their feelings out, or like David, filter them out with SSRIs. After Benji leaves the table, the group’s divorcee Marsha (Jennifer Grey) comments, He’s clearly in pain (you can decide if she means from his grandmother’s death, or his own demons). David’s reply is classically Jewish: Yeah, but isn't everybody? I figure we all are, so there's no need to burden everybody with mine.

There’s actually a hint of competitiveness in the act of grieving their shared grandmother, too, which feels bizarrely real. Who’s sadder than who? Who was closer? Who did she love more? David seems taken aback that Benji phoned their grandmother every Thursday without fail. Later, he’s rapt by a story Benji tells him about a time she slapped him.

When they finally find her past Polish home, they stand in a concrete driveway, staring at her front door with no real clue how to find closure. They decide to place stones on her doorstep, only to be told off by a neighbour – the stones could be a hazard to the old woman who lives there now. Someone else’s grandmother, who’ll also soon be gone.

Jesse Eisenberg’s a highly aware filmmaker, and his light touch helps A Real Pain soar. You can tell this story means a lot to him: Eisenberg’s ancestors were Polish Jews, and he applied for Polish citizenship in 2024. The final scene was even filmed at the exact same apartment that his predecessors fled from at the outbreak of WWII. How’s that for authenticity?

It might seem risky to lay down a carpet of lively banter before walking your characters (and your audience) through hushed scenes of a concentration camp, preserved exactly as it was 80 years ago. But it works. Despite its setting, A Real Pain springs from a place that celebrates the indefatigable nature of the human spirit and all its Benji-like quirks. It boasts a balance of humour amid an anguished history that’s properly uplifting.

If you’re after an incisive examination of generational trauma, or an unflinching Holocaust story, there’s better films for that. But to be fair, A Real Pain isn’t looking to sit on a double bill with The Zone of Interest. Benji and David’s tour ends with a tight and honest embrace, and it’s emblematic of this warm hug of a movie. A Real Pain affirms that it’s HARD to touch and feel and process our pain, past or present, big or small. And that’s okay.

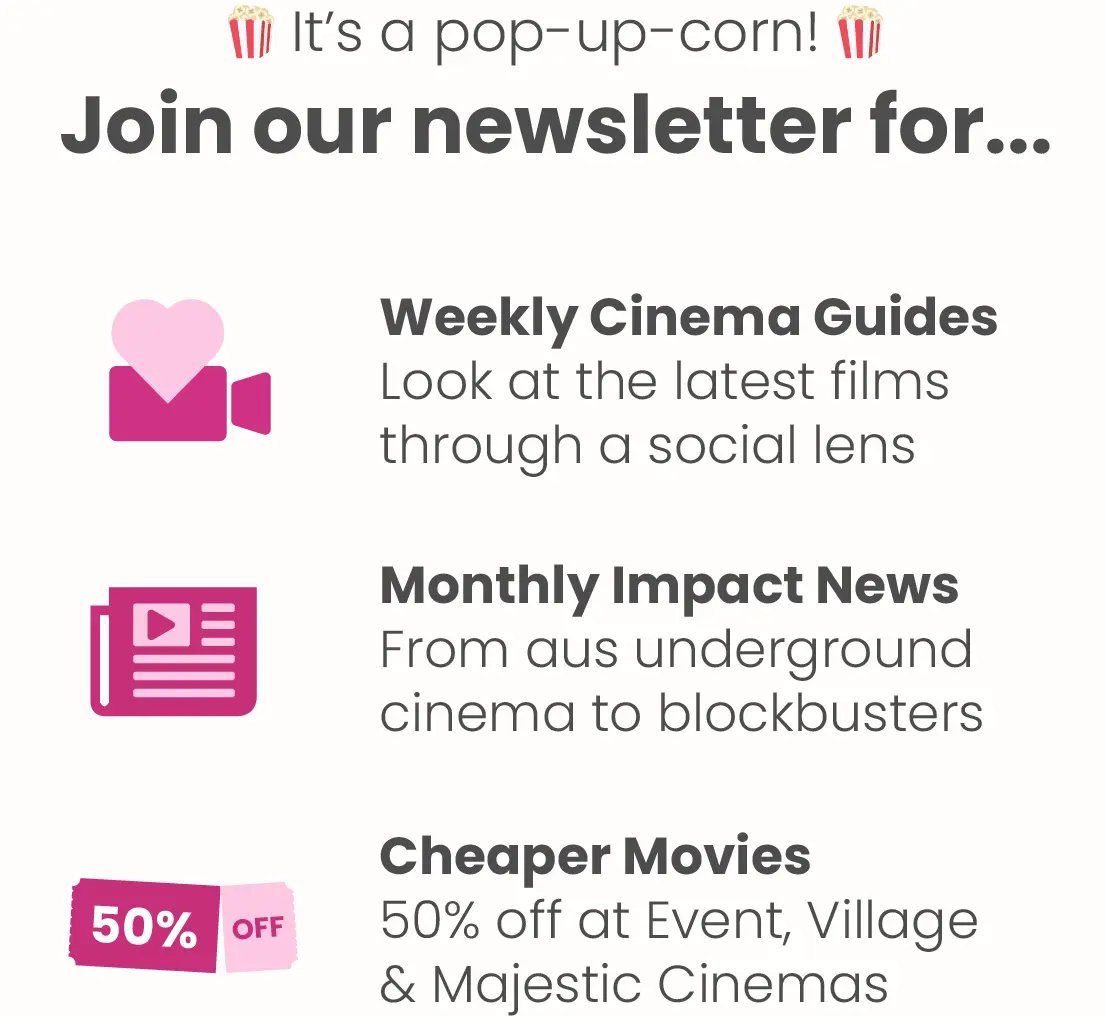

Keen for that deal to catch A Real Pain in cinemas?

GRAB YOUR DOUBLE PASS DEAL!