Popcorn Planet: Five Movies that Changed the World For Good

From a nervous first date to whiling away a rainy afternoon, the human race fell in love with cinema over a century ago. We examine the films that have reached past pure entertainment - challenging and awakening us in ways that led to irrevocable change.

good.film

4 years ago

Share

Who among us doesn’t love escaping into a good old feature film for a few hours? Whether in a packed cinema for that maximum-communal-joy feeling, or curling up in a favourite spot totally solo, movies are a unique pleasure that harness our ability to be transported by illusion. But it’s not all popcorn and plastic spoons. If you’ve read our guide to social impact entertainment, you’ll know that cinema has the power to do more than simply entertain: there’s a superpower in that celluloid to change our minds, our behaviours, and our world.

With a non-fiction narrative and (usually) a clear agenda, it’s no wonder that documentaries are a natural format to kick some real-world change into gear. With some docs, the impacts can be quantifiable and speedy. Take Morgan Spurlock’s Super Size Me – which proved so alarming that McDonald’s nixed its ‘super-size’ option weeks after the film’s release – or Bowling for Columbine from Michael Moore, whose relentless questions prompted KMart executives’ decision to stop selling ammunition permanently after meeting the filmmaker. For other documentaries, their impact is less immediate: you could describe them as planting strong seeds that shift opinions over time. Jennie Livingston’s seminal Paris is Burning is a great example, shining a disco-ball reflected light on New York City’s rampant homophobia and transphobia via the 1980s drag scene; so is Davis Guggenheim’s An Inconvenient Truth, the doco that’s widely acknowledged as jump-starting our awakening to the realities of climate change.

But the inspirational lure of feature films - that mystical alchemy of fictional characters in flickering frames, adjusting our brain’s chemistry in real time - has made some surprising impressions over the years too. Did you know that the enormous box-office success of Top Gun gave the US Navy the (genius) brainwave to set up recruitment stations outside theatres, snagging pumped-up wannabe pilots as they left the cinema adrenalized? It led to a 500% boost in Navy recruitment numbers in the year following the film’s release. Or that the ‘Day of the Dead’ parade staged in the opening scenes of 2015’s Bond outing Spectre didn’t actually exist - until the Mexican government got so many requests from tourists wanting to see one, that they instigated an annual parade in real life?

A side note here: entertainment’s impactful abilities aren’t just limited to cinema. The writers of the 1940s ‘Adventures of Superman’ radio serial needed a new foe after the Nazi defeat, and settled on the KKK as villains - flatlining their recruitment within weeks. And the lavish on-screen lifestyle of 80’s TV smash Dallas - one of the only Western shows allowed in communist Romania - has been widely credited with inspiring oppressed Romanians to overthrow the brutal Ceausescu regime. Impressive, no?

These spirited examples got us thinking: what other films have made a true, lasting impact on us, the human race? Which movies have… not just got us thinking, not just changed our minds… but changed a lot of minds? Changed a global perception around an issue, and ushered in a new era of awareness or acceptance?

We’ve donned our SCUBA* gear and done a deeper dive to find the movies that have hammered a notable, much-needed imprint into our collective social consciousness across a range of causes, from racism to female empowerment and animal rights. Some entries might surprise you - there were some healthy debates here at Goods HQ! - but one thing you can’t deny is their power. Behold: our list of 5 movies that changed the world (and some worthy runners-up that kept the party going).

*SCUBA in this case meaning Socially Conscious, Unflinchingly Brilliant Art ; )

In the Heat of the Night

Norman Jewison, 1967

Cause: Racism

It's been described as “defining”, “riveting” and “a landmark in the representation of African-American masculinity.” Others cite it as one of the most revolutionary acts committed to film.

While some movies are renowned for their overall impact - like the rest of this list - there are rare films that are not only powerful, but contain definitive moments that change the game. Like flicking a switch, a few feet of celluloid are sometimes enough to shock a generation into a new paradigm. Decades before our own backyard version was delivered, audiences were stunned by the slap dished out to a white plantation owner by an indignant, retaliatory Sidney Poitier. Director Norman Jewison later referred to the moment as “a slap that echoed around the world”.

It’s fair to say that In the Heat of the Night - a murder-investigation police procedural and “North vs. South story” - was in the right place at the right time. Writing for the Library of Congress, Michael Schlesinger appraised the film’s flashpoint release: “Seldom has a movie had such perfect timing. The Civil Rights movement was at its peak, with massive legislation passing on one hand and riots occurring on the other.” Martin Luther King was assassinated on April 4, 1968 - four days before the Academy Awards were poised to name the film Best Picture of the Year.

It wasn’t only on the streets that racial tension was reaching a boiling point. Poitier was an established, bankable leading man at the peak of his career, but that didn’t mean he wasn’t at risk – he was about to become the first black man to play a detective in any feature film. Famously, he refused to shoot the Mississippi-set film in the southern state for real; 3 years earlier on a publicity tour, he was chased by the KKK in a pickup truck and nearly ran off the road. When Jewison finally convinced Poitier to shoot for 3 days in Tennessee, he slept with a gun under his pillow. These very real tensions are harnessed and infused through the film’s 110-minute runtime. Writing for Senses of Cinema, Joanna Di Mattia recognises that “a feverish tension crackles in each frame … [the film is] very much an urgent product of its time.”

So when Poitier’s savvy detective character, Tibbs, interrogates racist landowner Endicott in his orchid-house (while black ‘workers’ toil outdoors), the mood is already one of mistrust. When Endicott deems Tibbs’ questions have gone too far, he slaps him in the face out of frustration. In the same second, Tibbs slaps him right back. The retaliation was unscripted, but Poitier insisted. Crucially, he asked for (and received) a guarantee the scene would appear in all prints of the film. He’d learned from experience: 2 years earlier, MGM had needlessly trimmed out a brief interracial kiss from his romance A Patch of Blue for every theatre below the Mason-Dixon line.

For the first time, audiences saw an African-American man physically strike a white man in a modern mainstream American film. The power of that moment to shock and awaken was immediately apparent: “Tibbs’s hand across a white face reclaims black male dignity”, wrote Joanna Di Mattia. “Not just angry or defiant, it’s an expression of what will no longer be tolerated in human relations.” According to film historian Mark Harris, “During the film's initial run, [stars] Steiger and Poitier went to [see] how many black and white audience members there were, which could be immediately ascertained by listening to the former cheering Tibbs's retaliatory slap and the latter whispering "Oh!" in astonishment.”

At a postponed ceremony, In The Heat of the Night won the Best Picture Oscar for 1967 – a year that saw the release of iconic movies like Guess Who's Coming to Dinner (also starring Poitier), Cool Hand Luke, The Dirty Dozen, Bonnie and Clyde, and The Graduate. It holds a 95% critic’s rating to this day, and in 2002, the film was preserved in the US National Film Registry as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant". Poitier’s classic line "They call me Mister Tibbs!", delivered with fiery defiance, is frequently cited in the Top 20 movie lines of all time. (Notably, the film marked a first in racial equality behind the scenes too: it was the first major Hollywood film in colour that was lit correctly and considerately for an actor with dark skin).

55 years on, there’s little doubt that In the Heat of the Night remains a relevant and incisive piece of cinema as a whole - yet it’s just a few powerful seconds of the film that cement its place in history like a whipcrack. Mark Harris opined to Slate that “the speed, the force, and the utter sangfroid of that second slap made it a milestone in the history of black representation in Hollywood cinema.” To bookend with the words of Roger Clarke: “The world changed with that one slap.”

Blackfish

Gabriela Cowperthwaite, 2013

Cause: Wild Animals

Animal welfare documentaries have grabbed our attention before - notably The Cove in 2009 - but the debut of Blackfish at 2013’s Sundance Film Festival proved incendiary. The story of Seaworld’s captive orca shows led by 5-tonne ‘star’ Tilikum, and the tragic death of orca trainer Dawn Brancheau caused by the powerful mammal, could at first glance be seen as another expose of the notorious “killer whale”. In reality, orcas are neither whales, nor have they ever caused a verified human fatality in the wild. Nat Geo calls them “highly intelligent, social mammals that have long been a part of marine park entertainment, performing shows for audiences. However, it's become increasingly clear that orcas do not thrive in captivity.”

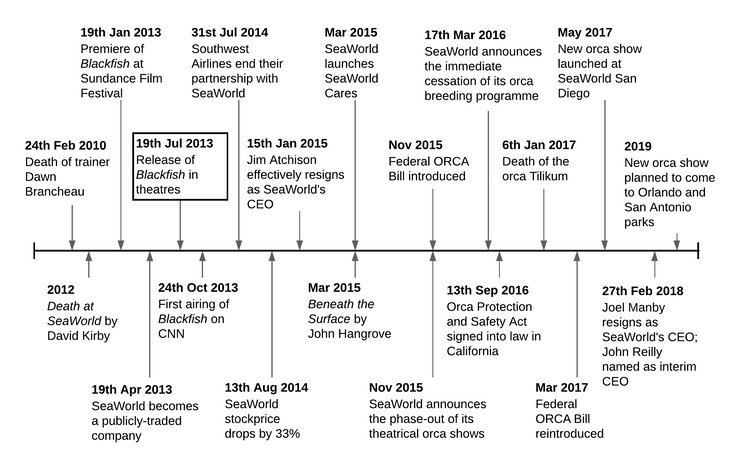

Blackfish brought this fact into sharp relief, pulling back the curtain to reveal the inhumane (and unethical) practices Seaworld used to keep wild animals in captivity for entertainment. In the wild, orcas swim upward of 150 kilometres per day - but after being taken from his mother in the Icelandic seas at age two, Tilikum was confined to a tank less than 50 metres long. He was routinely chased and attacked by other captive orcas, and endured a life of physical and psychological abuse. Environmental biologist Laura Thomas-Walters of Stirling University wrote that “Tilikum’s aggression [was] symptomatic of post-traumatic stress, induced by a life in captivity.” Seaworld denied the allegations, a corporate line that would come back to haunt the company in 2020 to the tune of $65 million - the price of settling a lawsuit brought by the park’s investors, who alleged Seaworld had lied about the impact the film had on its finances.

The documentary proved such a flashpoint, it spawned a new namesake for media that sparks change: “The Blackfish Effect.” In what may be the best example yet of genuine social impact entertainment, the Blackfish Effect saw horrified audiences vote with their morals and their wallets. On social media, the hashtag #EmptyTheTanks caught alight. Animal activists protested outside the park gates, music & performance acts cancelled upcoming Seaworld gigs, and corporate sponsors dropped their partnerships with the company. In the 12 months following Blackfish’s release, SeaWorld’s attendance plummeted by one million visitors. The company announced an 84% fall in income and saw its share price drop by 33%. The following year a bill banning the use of ‘show’ orcas in California received over 1 million signatures. As the Centre for Media & Social Impact wrote: “The film’s advocacy [for] orcas in captivity issued a clarion call… the story evoked empathy, an emotional response… a powerful driver of action.”

My Green World summarised the impact this way: “The Blackfish Effect achieved something profound. It has heightened awareness for fellow sentient beings, transformed the way that the public views marine parks, and redefined what the public previously considered light entertainment.”

The Blackfish Effect continued in the years after the doc’s release, with Seaworld announcing in 2016 that they would close their captive orca breeding program and phase out orca shows entirely, and in 2020 that they would put an end to trainers riding dolphins in their performances. It was a win for animal activists, who’d been campaigning for the stunt to be abandoned for years. As Laura Thomas-Walters concluded: “By … creating an emotional bond with viewers through the plight of Tilikum, Blackfish achieved what researchers have only speculated about when it comes to the potential of documentaries – sparking widespread activism and, ultimately, change.”

Honourable Mention: Bambi

David Hand, 1942

“You mean… the cartoon?” Yes, really. Disney’s beautiful animation, produced during the throes of WWII, remains an endearing classic, still holding a 91% on Rotten Tomatoes to this day. You’d be forgiven for getting misty when you recall the famous scene in which a mother deer is killed in front of her baby – but what you might not know is that the film led directly to deer hunting in the US dropping by half.

Schindler’s List

Steven Spielberg, 1993

Cause: Genocide

Widely regarded as Spielberg’s masterpiece, and described as “a near-documentary” by Sight & Sound’s Philip Strick, Schindler’s List stunned 1993 audiences with its harrowing power. Though far from the first film to depict the Holocaust, the real-life story of vain German businessman Oskar Schindler covertly turning his factory into a refuge for Jews provided a deeply human insight that proved impossible to forget. As reviewer Susan Stark wrote, the film: “insinuates itself so deeply into your consciousness that it offers not vicarious experience but instead, direct experience.”

Famously, Steven Spielberg - whose family were Orthodox Jews, and whose father had lost close to twenty relatives in the Holocaust - refused to take a cent in salary or profits for producing and directing the film, calling it “blood money”. Instead, Spielberg founded the nonprofit Shoah Foundation, which gathers and preserves the testimonies of Holocaust survivors and witnesses, using these to deepen understanding of the genocide. The foundation currently stores over 55,000 unique video testimonies. As the Shoah website states: “Our education programs bring the voices of survivors into classrooms, impacting future generations to build a better world based on empathy, understanding and respect.”

Incredibly, before Schindler’s List, the Holocaust was only mentioned as a “minor addendum” when American history teachers taught students about World War II. That all changed after the film’s release in December 1993. According to the Pennsylvania Holocaust Education Council, the film “was instrumental in rejuvenating Holocaust education and raising awareness.” Speaking to the Jewish Exponent, history teacher Jennifer Kugler said: “One of the things [the film did] was show that the Holocaust is not about the number 6 million. It’s about the individuals, the names, the people — it’s about their stories.” For Holocaust survivor Rena Finder, one of the youngest people on Schindler’s real list, the film was a cathartic experience: “It is almost impossible to put into words the immensity of the influence of the movie. We felt that, all of a sudden, it was OK to talk about being a survivor, because people were curious — they wanted to know what happened.”

Commonly cited as one of the greatest films ever made, Schindler’s List won over 90 international awards (including 7 Oscars), grossed $321 million worldwide, and was inducted into the US National Film Registry. But far more importantly than earnings or acclaim, the film sparked a fresh wave of education about this unimaginable genocide – and provided no small sense of peace for the untold numbers of Jews affected around the world. Or as Rena Finder put it, speaking about the film in 2013: “[Schindler’s List] is like a tree that blooms and leaves its flowers all over the world. Whoever watches it is changed.”

An Unmarried Woman

Paul Mazursky, 1978

Cause: Female Empowerment

Paul Mazursky’s divorce drama could be considered quaint if remade today - but that remake wouldn’t have a career-defining central performance from Jill Clayburgh, described as “one of cinema’s most authentic portrayals of womanhood”. Navigating an unexpected divorce, Clayburgh’s Erica embarks on a journey of self-discovery and self-reclamation notable for its realistic depiction of sex, grief, therapy and ultimately, acceptance.

Radical for its time, An Unmarried Woman was hailed as cinematic flashpoint for feminism, and retrospective reviews have included such praise for the film as being “a signifier of feminist freedom without becoming didactic or trite.” The film broke open a groundswell of female awakening, affirming the hushed-tones truth that they weren’t ‘worthless without men’ (and prompting many to leave certain men that were).

According to Janet Maslin, writing for The New York Times, “a weeping fan approached Clayburgh in 2002 to exclaim ‘My God, you’ve defined my entire life for me!’ – and that experience was apparently not unusual for her.” It’s for the untold thousands of other women empowered by her performance that An Unmarried Woman rightfully belongs in feminist cinema history.

Honourable Mention: Alien

Ridley Scott, 1979

Released one year to the day after An Unmarried Woman, these films aren’t exactly a natural double bill. Yet the only hesitation we had in giving Alien this spot was pinching it from Ridley Scott’s other seminal feminist masterpiece, Thelma & Louise. Originally written as a male lead, the masterstroke in casting created a stone cold sci-fi classic that made over 10 times its budget. Without Ellen Ripley, it’s debatable we would’ve seen iconic female heroes like Sarah Connor, Trinity, Wonder Woman or Katniss Everdeen.

Writing for the Independent, Arifa Akbar stated that Ripley acted as “a mirror for the gender shifts taking place outside Hollywood”. Sigourney Weaver herself agrees: "I think it was taking the pulse of society at that moment; we were another expression of how our world was changing. Women were agitating to be in the army, to work in warehouses and as truck drivers." As a result, Weaver is often credited for bringing feminism to the sci-fi space – and if you ask us, here on Earth to boot.

Philadelphia

Jonathan Demme, 1993

Cause: AIDS & HIV

It’s a misconception that Philadelphia was the first film to tackle AIDS. As early as 1985, Emmy-winning TV movie An Early Frost was seen by 34 million Americans; 4 years later, Longtime Companion became the first wide-release theatrical film about AIDS and picked up an Oscar nomination. What set Philadelphia apart as a landmark film was its punching power: the heft of a major Hollywood studio in Columbia TriStar; the cachet of a director hot off Best Picture & Director wins in Jonathan Demme; and the appeal of a global box-office star in Tom Hanks - in a role some labeled as career suicide.

We’re the first to admit Philadelphia isn’t a perfect movie. The film attracted criticism for Hanks’ character’s unrealistically supportive family, its broad-strokes villainy of the legal firm that fired him, and other convenient Hollywoodisms that ignored the nuanced reality of being gay - much less living with AIDS - in the 90s. Many in the gay community also felt slighted that, aside from a slow-dance, the film was overly coy about showing any physical romance between Hanks and his characters’ partner, played by Antonio Banderas (a bedroom scene was filmed, but cut for time).

But the filmmakers knew there was no sense in convincing those with lived experience of the disease: in a time when AIDS had killed nearly 250,000 Americans – and was still insensitively referred to by many as “the gay plague” – they needed to change prejudiced minds. As Demme stated when retrospectively quizzed about their so-called ‘straightwashed’ approach: “We wanted to reach the people who couldn’t care less about people with AIDS. That was our target audience.” Hence, the ‘everyman’ casting of Hanks, the inclusion of ‘relatable’ music from rock legends like Bruce Springsteen, and the film’s cautious handling of intimacy.

The tactic worked. Philadelphia took in over $200 million worldwide, was screened at the White House, and Hanks’ Oscar speech was watched live by over 46 million in the USA alone. But more importantly, the film changed the national conversation about AIDS. Jodie Howard wrote in Cinema of Change: “Undeniably, the impact of Demme’s film was extremely significant in initiating, on a larger scale, the conversation about AIDS that much of America had no desire of entertaining.” Writing for Smithsonian Magazine, Holly Millea agreed: “the film was a catalyst for conversations, acceptance and other film projects that might never have made it out of the closet. Thanks in part to that kind of AIDS education and awareness, the stigma of the disease is no longer as strong.”

But perhaps Hanks himself summed up the impact of Philadelphia best: “I think the movie was made for people who thought they didn’t know anyone who died of AIDS. And after the movie, they knew someone who died of AIDS.”

If you’re keen for even more examples of entertainment that changed the world - or itching to tell us what we missed! - we’ve got you. Sign up at good.film to find inspirational movies exploring a variety of causes. Vote on movies and streaming series for causes you care about. Create watchlists and share them with friends to keep the conversation going. Help make change where you feel it matters most - and inspire others to do more good!